I’ve never met Joe Biden and doubt I ever will; we hardly run in the same circles. (Can’t speak for him, of course, but I can tell you, unequivocally, I don’t run anywhere these days.) I’ve been thinking about him a lot lately, however, since there has been quite a bit of chatter regarding his fitness to run for a second term as President of these United States. As I write this, a great many people are suggesting that, at the age of 81, he has lost a step or two, both physically and mentally, and should be thinking more about retiring to Rehoboth Beach, Delaware than to reporting for work every day in the Oval Office. Much of these thoughts have surfaced after his poor performance against Donald Trump in their televised debate.

At 75, I am closer to the age of Mr. Trump (who, at 78, is also no spring chicken) than that of President Biden, but I can understand people’s concerns. I cannot imagine working even part-time at my age, let alone long, stressful hours at a job where so many decisions have the potential to impact the lives of millions of people around the world. Prior to that debate, there were questions about the Presidents’ age, but after his poor performance, when he fumbled and seemed to lose his train of thought, there are now myriad voices calling for him to cede the race to a younger person.

Needless to say, I have no idea what was going on with Mr. Biden that night, or in the days and weeks leading up to the debate. Nor can I speak factually about his mental acuity. But I can state, with certainty, that the very best of us can have a bad night, unexpectedly, at any point, and I would like to illustrate this by telling you about a baseball game I attended nearly sixty years ago.

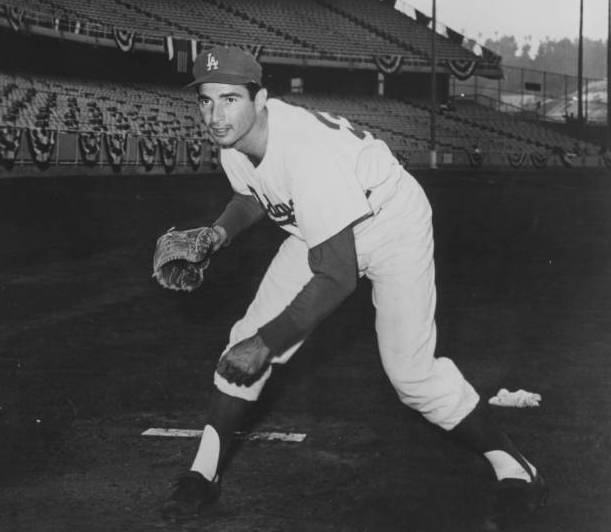

If, by chance, you are not familiar with a lefthanded hurler named Sandy Koufax, or if you’ve just heard the name but don’t know much about him, let me tell you that he was one of the greatest to ever toe a pitching rubber. In a six-year period, from 1961 through 1966, he put up incredible numbers: 129 wins against just 47 losses, a winning percentage of .733; a 2.19 ERA compiled over almost 1,633 innings; five consecutive ERA titles, with three of them coming in under 2.00; four no-hitters, capped by a perfect game; three Cy Young awards, one MVP selection, along with two years as the MVP runner-up. If you think of recent superior pitchers — Greg Maddux, Clayton Kershaw, Pedro Martinez and Randy Johnson, for instance – he was there long before them. And he was instrumental in his team, the Los Angeles Dodgers, winning four National League pennants and three World Series championships.

For more than half a century, there were sixteen teams in major league baseball, eight in both the American and National leagues. That changed after 1960, when the AL chose to immediately add a team in Washington (replacing the original Senators, who had relocated to Minneapolis) and Los Angeles. Not to be outdone, the NL expanded (beginning in 1962) to Houston and New York, which had lost both the Dodgers and Giants to the west coast after the 1957 season. And that Big Apple team, the Mets, became historically bad – they lost 120 games in their inaugural season, and were so out-classed that they finished 18 games behind the Cubs, who “only” lost 103 times. The Mets lost over 100 games in five of their first six seasons, and when they “progressed” by failing to reach the century mark in 1966, they still dropped 95 contests. All told, they lost 648 games from 1962 through 1967, an average of 108 per year. As I said, historically bad.

The Dodgers, meanwhile, were outstanding, as we mentioned a moment ago, due in large part to those eye-popping numbers posted by Koufax. And when he was called on to pitch against the Mets, the Brooklyn-born southpaw was at his very best. He beat them 13 straight times until finally losing one in August of 1965. Overall, he posted a 17-2 mark against the Metropolitans, throwing 162 innings (over 20 starts), striking out 173 (against 42 walks), with five shutouts and an ERA of 1.44. I would use a more descriptive word here than “dominating,” but I don’t think it exists.

Which brings us to 1966. The reigning World Series champion Dodgers came into Shea Stadium in late August involved in a razor-close pennant race with the Pittsburgh Pirates and San Francisco Giants, who were tied atop the National League, just a game ahead of LA. The Mets, meanwhile, were practically assured of their fifth straight sub-.500 season, but were working to avoid 100 losses for the first time (which they did, as we have seen), and reaching 8th place (no luck there). On a Monday evening, nearly 40,000 people saw the Mets triumph, 5-3, but the Dodgers had to have been confident they would leave New York with a series split, because Sandy Koufax would be taking the mound on Tuesday, August 30.

My friend Jerry and I decided to go, and we were joined by my thirteen-year-old sister, who was (and still is) four years younger than me and was not a huge baseball fan, but appreciated the significance of this game in this pennant race. Besides, school was still out, we did not have to be up early the next day! So the three of us took the subway out to Shea Stadium and joined nearly 51,000 others to watch this game. I can guarantee that no one at the ballpark that night realized it would be the final time that Koufax would face the Mets in his storied career.

We sat in the upper deck on the first-base side. Because we were silly teenagers, we brought noisemakers, thinking that we could, perhaps, distract Koufax or put a hex on the Dodgers or, in some way, affect the outcome. Uh huh. Oh well, our hearts were in the right place.

The Mets started a young lefthander in only his second major league season, Tug McGraw. He had to have been excited, pitching on his 22nd birthday against the great Koufax, which may have led to his giving up two runs right away – he walked the leadoff man, shortstop Maury Wills, and then first baseman Wes Parker put one into the seats. Centerfielder Willie Davis followed with a double, but then McGraw settled down and retired the side.

(By the way, these specific details are not coming from my memory, nor from my scorecard, which has long since bitten the dust. Thank you, baseball-reference.com!)

Koufax put the Mets away one-two-three, and we hoped that McGraw could keep the game close. He was not up to the task, which may be why, by 1969, he had been moved to the bullpen, where he would flourish, saving 180 games over a 19-year career with the Mets and Phillies. On this night, he gave up a leadoff double to catcher John Roseboro, walked light-hitting infielder John Kennedy, and then gave up a single to Koufax, a career .097 hitter. An excellent relay cut down the slow Roseboro at the plate, saving a run, but ending McGraw’s night; he had only been able to get four outs.

Mets manager Wes Westrum brought Bob Friend in from the bullpen. Friend, a husky right-hander, was at the back end of a fine career. He had been a mainstay in the Pittsburgh Pirate rotation for many years, reaching the double-digit victory total nine times, and earning three All-Star Game selections. But the previous winter, the Bucs had traded him to the Yankees, and by June the Mets picked him up in a straight cash deal. He wound up the season 5-8 as both a starter and reliever, and would be released in October, ending his career just three wins shy of 200. On this night, the 35-year-old Friend came into the game with runners on first and second and just one out, and he met the challenge, retiring Wills and Parker without any of their teammates crossing the plate. Up in the stands, we breathed a sigh of relief, even though we were still down by two.

I consider myself to be pretty knowledgeable about baseball, and I was definitely a fan of the Mets in the 1960s, but I have no recollection of an outfielder named Bill Murphy. I mention him because he started in center field that day, batted fifth, and in the second inning, he got a base hit off Koufax. (Westrum might have wanted only righthanded batters in the lineup that night.) It came after Jim Hickman, normally an outfielder but playing first that day, led off the inning with a walk. Murphy moved him to second with his hit and then, inexplicably, Koufax walked two more batters, forcing in a run. Now, it’s not like Sandy never walked anybody; over his career, he averaged a little better than three free passes per nine innings. But it was very unlike him to walk in a run. The next three batters left all three runners stranded, however, and LA still had the lead. But this was our first clue.

Friend retired the Dodgers in the third, and the Mets went back to work. All-Star second baseman Ron Hunt led off with a single, and third baseman Ken Boyer, the 1964 MVP (while he was with the Cardinals), blasted a double, moving Hunt to third. The crowd’s cheers turned to groans as Hickman hit a grounder to Maury Wills, but the seven-time All-Star (and 1962 MVP) booted the ball, allowing Hunt to score with the tying run. What was going on here? Which of these teams was battling for first place? Murphy also hit one on the ground, and the Dodgers elected to get the sure out at first, which meant that Boyer scored and Hickman moved to second. This brought up the Maryland strong boy, outfielder Ron Swoboda, and he smoked a single up the middle, scoring Hickman and sending Murphy scampering to third.

Dodgers’ manager Walt Alston, a future Hall of Famer, slowly walked out to the mound and, to the delight and amazement of the nearly 51,000 fans in the stands, removed Koufax, another future Hall of Famer. We were amazed, Koufax had been knocked out in the third! This had never happened before, at least not in games the great southpaw had pitched against the Mets. We were witnesses to history, of sorts.

Righty Joe Moeller came into the game and, after getting shortstop Ed Bressoud to fly out, gave up a double to catcher Jerry Grote, clearing the bases. No more runs scored, but now the score was Mets 6, Dodgers 2.

A further play-by-play is not necessary, a brief summary will do. Four singles produced two more New York runs in the fifth, which the Dodgers countered in the seventh with a home run by pinch-hitter Wes Covington. But on this night, at least, the Mets were not to be denied, adding single runs in the seventh and eighth innings for their final 10-4 triumph. They tallied fifteen hits overall, including 11 singles and four doubles. Everyone in the lineup got a hit except for Jim Hickman and Tug McGraw (who never came to bat). Bob Friend even got into the act with a single, quite an accomplishment for someone who retired with a .121 lifetime batting average. This would, by the way, be the final win of Friend’s career.

And what about Koufax? Was this a sign that his damaged left elbow, ravaged by acute arthritis, would send him to a shocking early retirement less than three months later? Not really. In LA’s final 32 games, Koufax won six times, losing only once, leading his team from third place (after that loss to the Mets) to a second straight National League pennant. For the season, Koufax won a career-high 27 games, threw 323 innings (including 27 complete games), and posted an ERA of 1.73. All of those figures led the majors. He would pitch one more time, in Game Two of the World Series against Baltimore, and be defeated, 6-0. He gave up four runs, but three of them scored when center fielder Willie Davis made errors on two consecutive plays, making all those runs unearned. While Koufax was definitely outpitched that day by Jim Palmer (just days away from his 21st birthday), it was hardly embarrassing.

So what does this have to do with Joe Biden? Koufax had a bad night on August 30, 1966, but it did not mean he was no longer effective; after all, he won six games the rest of the season. In his recent debate with Donald Trump, I believe Joe Biden simply had a bad night; like Koufax more than fifty years earlier, he just didn’t have his good stuff. Now, don’t get me wrong, I am not denying that the President is an old man, or that he hasn’t slowed down during his time in the White House. But I do not believe that he should be forced to get out of the race for the Presidency. Sandy Koufax made the choice to retire, based on the condition of his elbow. Joe Biden should be allowed to choose, on his own, when to get off the mound for the last time.

Image: Unknown author – University of Southern California, California Historical Society, http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/p15799coll65/id/25788