The late catcher, coach and major league manager, Wes Westrum, supposedly said “Baseball is like Church. Many attend, few understand.” Some people attribute this quote to Hall of Famer Leo Durocher, but there can be no doubt who used the term The Church of Baseball. That was Annie Savoy, the character played by actress Susan Sarandon in the film “Bull Durham.” And the man who wrote the film, former minor league player Ron Shelton, decided the phrase would be the perfect title for a book about the making of the movie.

Baseball is, of course, a religion to many. In this vein, I was reminded recently of an experience I had, as a young man, that briefly wedded the two together.

Jewish people, like me, attend synagogues, not churches, but the concept is pretty much the same. And our holiest day is Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, when one is supposed to pray for forgiveness for all their sins of the past year. It always takes place very early in the Jewish New Year, and charges us to commit ourselves to becoming better human beings. One is supposed to spend all morning praying in the synagogue, returning in the evening for a concluding service. Oh, and you are also supposed to fast, beginning with sunset the previous day and lasting until the following sunset, a period of about 25 hours. To paraphrase the great sage Kermit The Frog, it’s not easy being Jewish.

For those of you whose knowledge of Judaism is limited to Jerry Seinfeld jokes, let me tell you there are three subsets to the religion. The Orthodox, as you might expect, are the most religious; the Conservative are not quite as observant, and the Reform are even less so. Since this piece is not a treatise on Judaism, that’s as far as we’ll go today, class, except to mention that my family identified as Conservative. You’ll see why this is germane momentarily.

Except for a period of about fifteen months when I was in graduate school, I lived with my parents until I was closing in on 29 years old. Even in the 1970s, an apartment in any of New York City’s five boroughs was expensive, and while my pay at WNET television was OK, it would only have afforded me a small flat in the poorer and more dangerous parts of town. Besides, I got along very well with my parents, and my mother was a great cook, why give that up? I am telling you this because the incident I am going to relate took place in 1973, when I was 24 and in the midst of this stay-at-home phase.

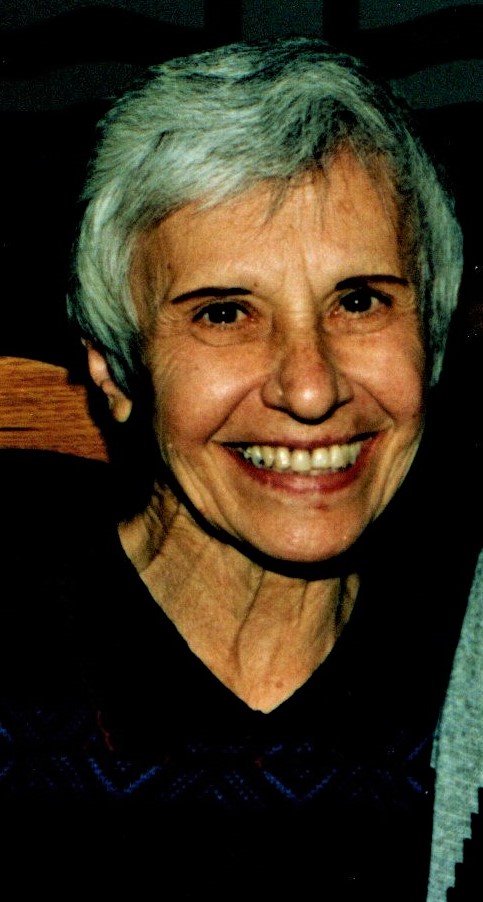

You already know that I am a huge baseball fan, but so were my parents. My father was a lifelong follower of the Chicago Cubs, despite having never been to the Windy City. My mother, having grown up in Pittsburgh, originally followed the Pirates, but eventually became a hardcore devotee of the Mets. There were times she fell asleep with a transistor radio by her ear as she listened to her team when they were out on the West Coast.

My mother also set the tone for the household in general. We only ate kosher meats and followed the Jewish dietary laws, known as kashrut. During the eight days of Passover, we had a separate set of dishes and silverware and did not eat bread at all, or anything that did not have the OU seal of approval from the Orthodox Union. And on Yom Kippur, we went to synagogue in the morning, fasted all day, and either walked or read in order to make the day go by.

All of which brings us to 1973.

After their shocking World Series triumph in 1969, the Mets had committed a mortal sin – they became average, finishing just a few games over .500, and in third place, in 1970, 1971 and 1972. And after a good start in 1973, things seemed to fall apart, and they spent most of the summer in the nether regions of the National League East. After play had concluded on August 30, they were ten games under .500 and dead last, with just thirty games left in the season. The only sign of optimism was the fact that the entire division was mediocre. The St. Louis Cardinals led the pack, but they were just three games over .500. The Pittsburgh Pirates, who had won the division for three straight years, were struggling to get their heads above water. The Mets, despite sitting at the very bottom, were only 6½ games out of first place. Though highly unlikely, another miracle was still possible.

The problem was that this team couldn’t hit, especially with runners in scoring position. In their first 132 games, they had compiled a record of 61 wins and 71 losses, and scored just 487 runs, an average of 3.69 per game. They had been shut out 14 times, including two separate occasions when they were blanked in back-to-back games. With bats in their hands they were pitiful.

But starting on August 31, everything unexpectedly came together. While they didn’t suddenly become an offensive behemoth, they scored 121 runs in 29 games (one game was rained out, so they wound up playing 161 for the season), an average of 4.17 per game. Still not spectacular, but it was right around the league’s average. And with their exceptionally strong pitching, the team sprinted in September like a horse racing down the stretch at Churchill Downs. They won 21 of their final 29 games for a record of 82 wins and 79 losses, winning their division by a game-and-a-half over St. Louis, the only other team in the NL East to finish at or above .500. (By contrast, four of the six teams in the NL West finished over .500)

The Mets had now won the right to face the Cincinnati Reds in a best-of-five series, with the winner advancing to baseball’s ultimate showcase, the World Series. The Reds were a major powerhouse, featuring future Hall of Famers Sparky Anderson (the manager), Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan, Tony Perez and Pete Rose. They scored 741 runs (4.57 per game) that led to a league-leading 99 victories. They were known by their nickname — The Big Red Machine.

The pundits all said the Mets had no chance.

However, that did not dim the enthusiasm of their fans, especially in our house. My mother was seriously excited… until I pointed out that the first game of the playoffs was scheduled for the afternoon of Monday, October 6, which was Yom Kippur. We were not allowed to turn on any electronic device, including a television or radio, no matter the importance of the ballgame scheduled to be played in Cincinnati.

My mother, however, was nonplussed. “We’re allowed to walk,” she said. “We’ll just walk over to Flatbush Avenue.”

Even if you have never set foot in Brooklyn, you may have heard of Flatbush Avenue. It is a long street that traverses much of the borough, and is filled with commercial establishments, as well as a high school, Erasmus Hall, from which I graduated in 1966. (Some notable alums include Barbra Streisand, the late actor Eli Wallach, former Oakland Raider owner Al Davis, singer Neil Diamond, basketball Hall of Famer Billy Cunningham, and chess champion Bobby Fischer.) But I knew what she meant – there were, at that time, quite a few electronics stores all along the street, and many of them had placed the latest-model television sets alluringly in the window. And after the Mets’ thrilling September dash to first place, they would all, undoubtedly, have their sets tuned to the ballgame.

They would all have their share of observant Jewish baseball fans. After completing our leisurely half-hour stroll to Flatbush Avenue, we found that we were not the only hungry but well-dressed people crowding around store windows. Fortunately, there were several viewing locations to choose from, and we found one that afforded us room and a decent view. My mother, being just under five feet tall, naturally got to stand right at the window, directly in front of the TV.

Please note the use of the word “stand.” The stores may have been kind enough to make sure their TV sets were tuned to the ballgame, but no one offered us chairs; after all, we were not patrons, we were gawkers and freeloaders. So we stood for two hours.

And we saw an outstanding game. The Mets, naturally, led with their ace righthander, Tom Seaver. The future Hall of Famer (311 career victories, 231 complete games, 3650 strikeouts and a lifetime ERA of 2.86) had won 19 games in 1973 and led the National League in ERA, strikeouts and complete games. After the season, he would win his second Cy Young Award. His mound opponent, however, was no slouch. Jack Billingham had also won 19 games, and led the league with his forty games started and 293 innings pitched.

The Mets came out swinging, and loaded the bases in the first inning on two singles and a walk. But a double-play ended the inning, causing my mother to use the only swear word in her vocabulary – “Damn!” (And on Yom Kippur, too! Add that to the list of things to atone for.) They made up for it in the next inning when Seaver – a good-hitting pitcher – cracked a double that scored shortstop Bud Harrelson, who had walked. Billingham had given up three hits in the first two innings, the September surge had certainly continued into October.

The Reds wasted a couple of opportunities, and in the bottom of the eighth, the Mets still had that 1-0 lead. But with one out, Pete Rose came to the plate. Rose, of course, was one of the game’s great stars; he had just won his third batting title, and his career-high 230 hits would propel him to the league’s Most Valuable Player award. But he was not considered to be a power hitter like his teammates Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan or Tony Perez. No matter, he took Seaver deep, and the game was tied.

Some of us sidewalk fans decided to leave, saying “it’s only a matter of time now.” My mother and I stayed, ever hopeful, sure that the naysayers were wrong. They weren’t. After getting the first batter in the bottom of the ninth, Bench ended matters with a blast into the leftfield seats. The Big Red Machine, getting their usual power and better-than-expected superb pitching, had won the series opener. (By the way, after getting three hits in the game’s first two innings, the Mets did not hit safely the rest of the game.)

We trudged on home. My mother was particularly upset, but that was not uncommon; she expected to win every game, and took losses hard. An old adage in baseball is to never get too high after a win or too low after a loss, a motto my mother was never able to learn. The loss, undoubtedly coupled with her hunger pangs, made our walk home seem interminable.

We did have a happy ending, however. The Mets won three of the next four games, including a Seaver-Billingham rematch in the deciding Game Five, allowing the team with a .509 winning percentage to defeat a club with a .611 mark. They then went on to the World Series against the Oakland A’s and went the limit against the defending champions, losing in seven.

For me, however, that was almost anticlimactic. Sure, I wanted the Mets to beat Oakland, but when I think of that 1973 season, my first thought is always Yom Kippur, walking to Flatbush Avenue, and standing and watching that baseball game with my mother. It is something I can never forget.